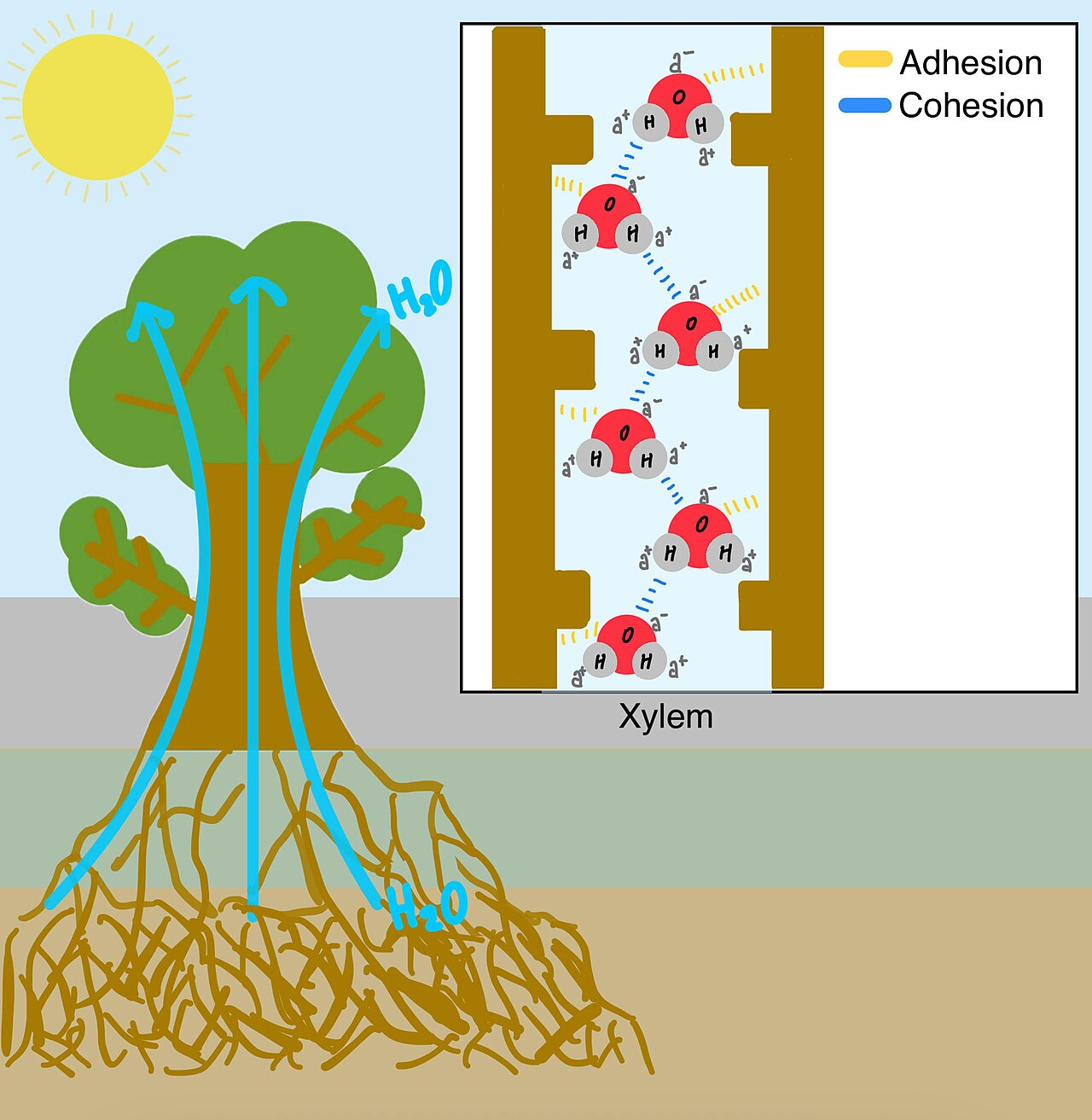

It occured to me when I was talking about Cotton, and Frost Flowers, that the ability of liquids to rise (or “wick up”) through a gap, a process known as capillary action, is central to a lot of life on Earth.

It’s why towels pick up moisture, why sap rises up plants and trees, and why damp rises up walls. The mechanism that drives capillary action is why the insects known as water-boatmen can walk on the surface of ponds, why rain falls in drops, and why liquid spilled on a surface forms a pool.

It all occurs because water exhibits a characteristic known as surface tension, and this happens because water is ‘sticky’.

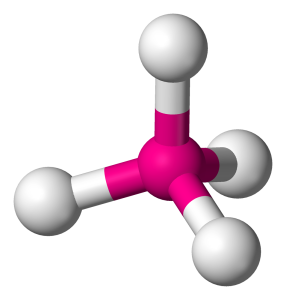

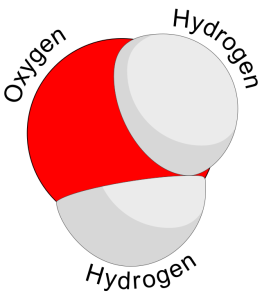

Each molecule of water is formed from two hydrogen atoms and an oxygen atom (H2O) which are stuck together by something called a polar covalent bond[1]. This is a type of bonding where atoms share electrons.

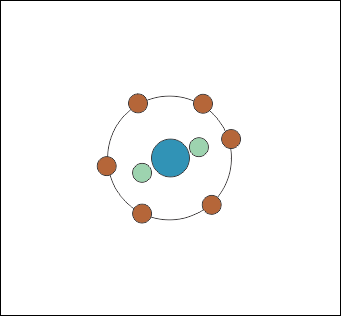

For those familiar with the Periodic Table, elements are most stable when they have full outer electron ‘shells’. The first electron shell holds two electrons, and the next one can eight, but oxygen only has six left to go in there (Fig. 1). Two stay tucked away closer ot the nucleus.

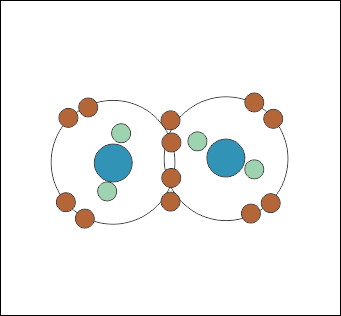

In the atmosphere, oxygen atoms pair up to share outer electrons so they both have eight (Fig. 2) which is why atmospheric oxygen is known as O2.

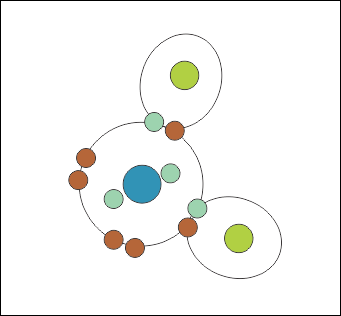

If you can get O2 close enough to hydrogen it will break up, and the oxygen atoms will share an electron with two hydrogen instead, so they both effectively have an extra one.

In the old ‘plum-pudding’ model of atoms – which you may have learned at school – you would imagine that the shared electrons fly around them both. It’s not really like that because electrons don’t really fly around atoms, it was a useful concept which doesn’t match up with reality, but you could consider that the little patch of energy that forms the electron jams itself in between them, so they both feel it.

You initially need to add enough energy to break the oxygen apart, but the bonds it makes with hydrogen require less energy, so if you mix oxygen and hydrogen and light it, you get energy released - in other words it goes Bang! Hydro-gen means water-maker. This might seem a nice clean way to power an engine using hydrogen because all you get as a waste product is water - which is true if you burn hydrogen in pure oxygen, but not if you burn it in air because air is mostly nitrogen, so you get various forms of nitrous oxide as well.

When you have ‘loose’ electrons around an atom they form a lower-energy state if they electrons sit together in pairs (Figs. 2 and 3). The reason for this is complicated and I’ll write another article about that.

This means the eight electrons around the ‘outside’ of the oxygen atom in a water molecule will form four pairs. Two of those pairs are the ones stuck to a hydrogen atom, and two are what are known as ‘lone pairs’.

Electrons repel each other, and so the pairs try to stay as far apart as possible.

While this is normally a feature of 'orbital' electrons in atoms, it can occur outside them. Electricity is a flow of electrons, and they typically flow in isolation, but if you can get them to join up to form pairs (Cooper Pairs[5]) they are able to flow without resistance, and you have what is known as superconductivity.

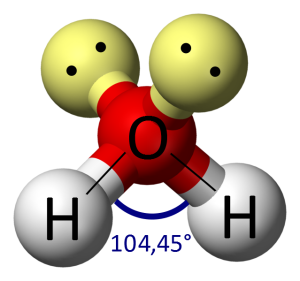

If you think about four objects trying to get as far apart as they can from each other on a circle, you would come to the conclusion that they drift to 90° apart, but this isn’t a circle, it’s a sphere. If you do the mathematics on that you’d expect them to stay 105° apart – like a tetrahedron (Fig. 4).

In a water molecule, two of these legs are Hydrogen atoms each sharing two electrons with the central oxygen, and two are just the force exerted by pairs of ‘lone electrons’ – electrons that pair up with opposite spins because that forms a lower-energy state.

When you look at that as a three-dimensional molecule, you’ll see that however you arrange the two lone pairs and the two pairs bonded to hydrogen there’s always an angle you can view it from where it looks like a V-shaped molecule (Fig. 5).

Neither the hydrogen nor the oxygen atom had an electric charge when they were loose, because hydrogen has one (positive) proton, and one (negative) electron to balance it, and oxygen had eight of each.

Now they’ve bonded, the molecule in total has the same number of protons and electrons, and is therefore still neutral in terms of charge.This all seems to make sense, but if the molecule has no overall charge, why do we say it is ‘sticky’?

The answer is: The oxygen atom pulls harder on the electrons it shares than the hydrogen atom does. In technical terms it’s more electronegative[8].

One effect of this is that the oxygen ‘end’ of the molecule is slightly more negative than the hydrogen end of it, because the oxygen atom keeps those two pais of electrons a bit closer.

This unbalances the nice even distribution of charge we’d expect, and that in turn causes two things to happen. Firstly, it means that the pairs of electrons don’t all repel each other evenly, so the angles between the four pairs of electrons don’t stay at 105°. The angle between the two hydrogen atoms settles down to 104.45° – known as the bond angle of water (Fig. 6).

These form a tetrahedral shape (triangular-based pyramid) with a slight distortion from the unbalanced charges caused by the oxygen atom pulling on the shared electrons harder than the hydrogen atoms do. The yellow balls are not atoms, they are just a representation of the ‘force field’ caused by the two unbonded pairs of electrons.

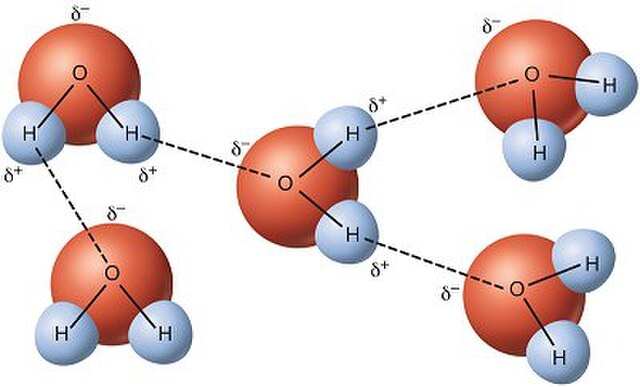

The fact that the hydrogen ‘end’ of a water molecule has a slightly positive charge compared to the oxygen end means water molecules are attracted to each other and to other molecules – a process known as Hydrogen Bonding.

Hydrogen bonds make water sticky![10]

Now we see that water molecules are slightly polarised, and therefore are able to stick together. This is a process known as hydrogen bonding[11].

Within the liquid the V-shaped molecules can form bonds in three dimensions because they can rotate, but at the surface they tend to form a lattice, which gives the water a skin. This surface tension allows light objects to sit on top of water (Fig. 8).

This skin is, of course, just made of water, but it is essential for the formation of droplets (Fig. 9). Without it, water would just spread out until it was one molecule thick.

To understand why surface tension is essential to the process of capillary action, we need to look at what happens when water meets a surface.

The forces which occurs between atoms or molecules in a liquid, and which hold it together, are known as cohesive forces. They’re not always hydrogen bonds like water. Liquids are also attracted to other materials by adhesive forces[15].

Unfortunately, most references to adhesive forces tell you what the word means, but don't tell you what the force actually is. It's an intermolecular force that arises from several factors, and is known collectively as Van der Waal's[16] force.

It creates a meniscus, which is the curved surface of a liquid which you see when it comes into contact with a surface (Fig. 7).

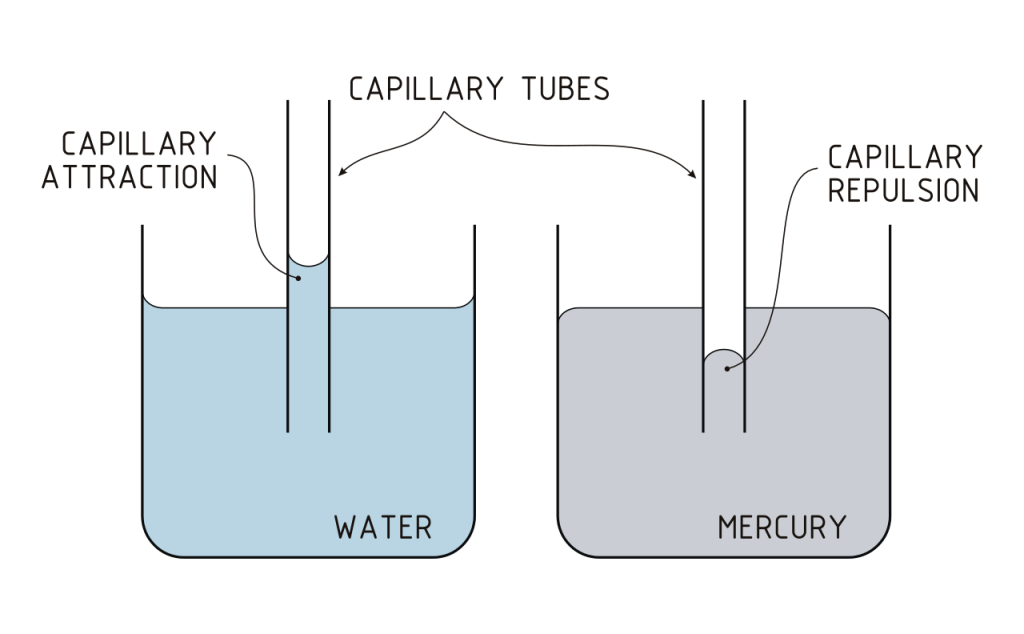

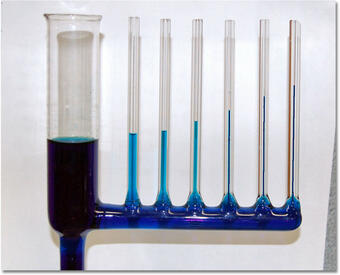

When the water is attracted to the sides of the tube in Fig. 10 it creates a curved surface, and the surface tension – the hydrogen bonding within the surface lattice – produces an upwards force. This is exponentially proportional to the diameter of the tube. You can see that a similar effect occurs where the water meets the sides of the container, but it is so wide that the surface has become flat. The rise of the water in the tube is inversely proportional to its diameter. The narrower the tube the further it rises.

The force is related to the diameter of the tube, the angle the water makes with the surface of the tube[19]. The smaller the diameter, the more curved the surface ‘skin’ is and this creates a larger force (Fig 11).

For other liquids, the capillary action operates according to the same rules, although the causes of the cohesive force within the liquid may be different. The cohesive forces within mercury, for example are the result of metallic bonding[20]

Capillary action depends on the relative strengths of the cohesive forces that hold the liquid together and the adhesive forces that attact it to the surface. When cohesive forces exceed adhesive ones, the meniscus is inverted and capillary action operates in reverse. In Fig. 10 the mercury is repelled from the surface.

If oxygen atoms didn’t pull electrons a little bit harder than hydrogen ones, water molecules wouldn’t be ‘sticky’, they wouldn’t form surface tension, vapour wouldn’t form raindrops, plants couldn’t take up water from the ground, and life as we know it would not exist.

Further Reading

Featured image: TiffanyChan0926, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- [1] https://chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_Chemistry/Introductory_Chemistry_(CK-12)/15%3A_Water/15.01%3A_Structure_of_Water

- [2] Steve Douglas – Public Domain

- [3] Steve Douglas – Public Domain

- [4] Steve Douglas – Public Domain

- [5] Brtiannica: https://www.britannica.com/science/BCS-theory

- [6] n.a., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- [7] Booyabazooka at English Wikipedia, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- [8] Science Direct, Electronegativity: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/chemistry/electronegativity

- [9] Riccardo Rovinetti, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- [10] Exploring Our Fluid Earth, Hydrogen Bonds Make Water Sticky: https://manoa.hawaii.edu/exploringourfluidearth/chemical/properties-water/hydrogen-bonds-make-water-sticky

- [11] https://chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Organic_Chemistry/Map%3A_Essential_Organic_Chemistry_(Bruice)/01%3A_Electronic_Structure_and_Covalent_Bonding/1.11%3A_The_Bonds_in_Water

- [12] J:136401, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- [13] JJ Harrison (https://www.jjharrison.com.au/), CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- [14] The Eloquent Peasant, CC BY 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- [15] Biolin Scientific: https://www.biolinscientific.com/blog/understanding-cohesion-and-adhesion-the-forces-behind-everyday-phenomena

- [16] Brittanica: https://www.britannica.com/science/van-der-Waals-forces

- [17] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/86/Capillary_Attraction_Repulsion_%28PSF%29_%28bjl%29.svg

- [18] USGS, Dr. Keith Hayward

- [19] Biolin: https://www.biolinscientific.com/blog/capillary-action-how-contact-angle-and-surface-tension-are-related

- [20] University of Illinois, Meniscus of Mercury: https://van.physics.illinois.edu/ask/listing/1746